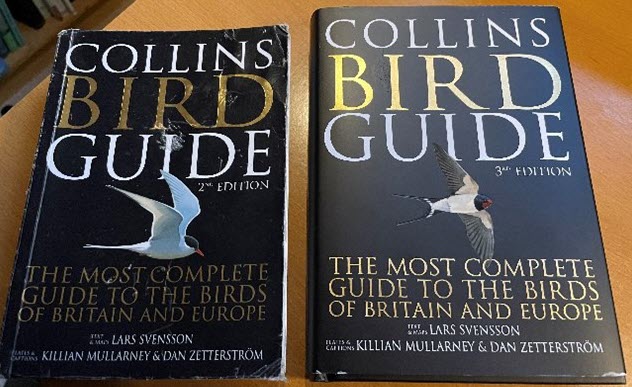

The Collins Bird Guide was first published in 1999 and instantly became the go-to guide for all birders. The 2nd edition was published in 2009 with a subsequent reprint with further amendments in 2018 (though not enough amendments to call it a 3rd edition). The long-awaited 3rd edition was finally published earlier this December. Is it still the go-to guide for birders?

The first thing to understand is that guidebooks with painted prints portray the ideal plumage of a species, whereas photographic guides present a snapshot image of that species at that particular time. Photographic guides often require many more images to capture the species plumage effectively, whereas guides which use painted prints can convey plumage differences in fewer images, though there will always be those birds which, in the field, appear different to those in the guidebook. Remember these guidebooks portray the ‘normal’ plumages for that species so it is still important to develop good field skills to pick out those identification points for comparison with the guidebook images.

The 3rd edition has 32 additional pages on the 2nd edition (2009) though only 28 additional pages on the 2018 reprint. What is interesting and a good addition are those species plates that have given more space with more larger images in varying plumages. Loons (divers), on pages 60-63, have been treated to this expansion and now include Pacific Loon in the main body of description.

The entire text and all maps have been revised and updated, such as Great Grey Owl and Ural Owl (page 232-233) which show amended distribution.

The taxonomy reflects the latest thoughts at the point of publication, but given the dynamic nature of avian taxonomy, this is already out of date. Page 70 refers to Yelkouan and Balearic Shearwater, however, recent research on genetic analysis suggests that these two species should be lumped together (BOU has yet to act upon this).

Many of the plates have been reprinted with a greater vibrancy and accuracy in the colour portrayal, which adds to the guides effectiveness in portraying plumages and thereby assisting with identification. Black Redstart (page 292-293) is one such species that has been updated and its images, when compared with the earlier edition, are clearly brighter and more defined. The addition of more subspecies, for this species, is a welcome addition.

Bird families which have been given more space or new plates include grouse, loons (divers), terns, owls, swifts, woodpeckers, swallows and redstarts amongst others. Of particular note are the new raptor plates which give more space, larger more vibrant images showing a wider range of plumages. A great example of this are the harrier plates (page 106-109) which when compared with the earlier edition are clearly brighter and more informative. The expanded text also reflects this improvement.

So, is this new edition worth acquiring? There is always going to be a bit of compromise when trying to include up to date information on bird species in a field guide but once again the authors (Svensson, Mullarney and Zetterstrom) have produced an excellent, updated guidebook which will become an essential companion to birders throughout Europe.

Dave Grant